Emerging Toxicological Threats in the U.S.: Xylazine, Nitazenes, Novel Sedatives, Synthetic Cannabinoids, Fentanyl Analogues, and Toxic Mushrooms

Omid Mehrpour

Post on 08 Dec 2025 . 22 min read.

Omid Mehrpour

Post on 08 Dec 2025 . 22 min read.

The landscape of drug-related poisons in the United States is rapidly evolving. New emerging poisons – from adulterants in street opioids to novel “natural” toxins popularized on social media – are challenging healthcare providers and endangering the public. In 2023, nearly 70% of overdose deaths involved synthetic opioids (primarily fentanyl), and now additional substances like xylazine and nitazenes are compounding this crisis. Meanwhile, novel sedatives (such as designer benzodiazepines), new-generation synthetic cannabinoids (e.g. “K2” or “Spice”), ultra-potent fentanyl analogues, and toxic mushrooms promoted via TikTok foraging trends are causing a spike in poisonings. This article introduces six of these emerging toxicological threats – explaining what they are, how they present clinically, the risks they pose, and insights into management. Our goal is an accessible overview for the general public, with the detail and references that healthcare professionals will find informative.

Xylazine is a veterinary sedative increasingly detected as an adulterant in illicit opioids; for a detailed fentanyl–xylazine response guide (naloxone limits, rescue breathing, harm reduction), see our dedicated post ‘Fentanyl + Xylazine (‘Tranq’): Why Naloxone Alone Isn’t Enough'

What is xylazine? Xylazine is a non-opioid veterinary sedative increasingly found mixed with illicit fentanyl. Because it is not an opioid, naloxone does not reverse xylazine’s effects (see the full response guide in our fentanyl–xylazine post)

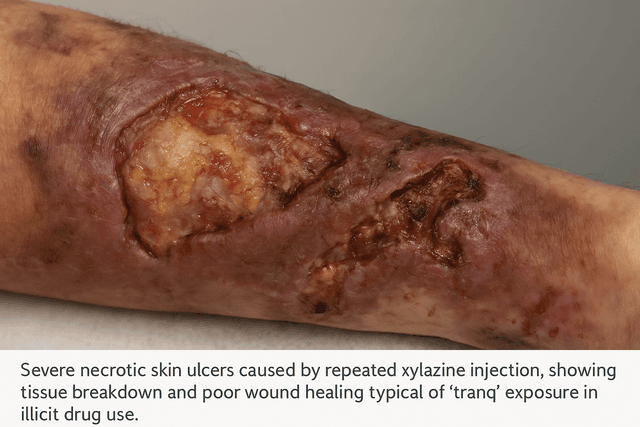

Why is it dangerous? Xylazine can cause profound sedation and cardiorespiratory depression and is strongly associated with severe, sometimes necrotic skin ulcers. Naloxone may improve ventilation if an opioid is present, but it will not reverse xylazine itself; for the full clinical and harm-reduction breakdown. (see:‘Fentanyl + Xylazine (‘Tranq’): Why Naloxone Alone Isn’t Enough').

Clinical presentation: Suspect xylazine when ventilation improves after naloxone but profound sedation persists, or when severe skin ulcers are present. Detailed clinical patterns and response steps are covered in our fentanyl–xylazine blog. (see:‘Fentanyl + Xylazine (‘Tranq’): Why Naloxone Alone Isn’t Enough')..

Management and response: Give naloxone for suspected opioid co-exposure, but expect that sedation and hemodynamic effects may persist and require supportive care. For step-by-step response (rescue breathing, when to call 911, wound considerations, harm reduction). (see:‘Fentanyl + Xylazine (‘Tranq’): Why Naloxone Alone Isn’t Enough').

Nitazenes are a class of novel synthetic opioids generating concern due to their extreme potency and growing presence in overdose cases. Chemically distinct from fentanyl, these compounds (examples include isotonitazene, etonitazene, and metonitazene) were originally developed in the 1950s for research, but never approved for medical use. Around 2019, nitazenes re-emerged on the illicit drug market and have proliferated since.

Potency and risks:

Many nitazene analogues are reported to be hundreds to thousands of times more potent than morphine, with some even stronger than fentanyl. For example, etonitazene is roughly 10–20 times more potent than fentanyl (up to 1000× morphine), and isotonitazene ~500× morphine. This extreme potency means that even minuscule doses can be fatal, causing profound respiratory depression. Illicit manufacturers have embraced nitazenes because they are relatively easy to synthesize and, by slightly tweaking chemical structures, producers can skirt existing drug laws (a game of “catch me if you can” with regulators). Nitazenes are often pressed into counterfeit pills or mixed into other drugs (like fentanyl, heroin, or stimulants), which leads to users ingesting them unknowingly. This is especially dangerous for opioid-naïve individuals who have no tolerance – a tiny hidden dose can cause a lethal overdose.

Clinical presentation: A nitazene overdose looks much like a high-potency opioid overdose: severe respiratory depression (slow or stopped breathing), unconsciousness, pinpoint pupils, and cyanosis (blue-tinged skin) from lack of oxygen. One distinguishing factor might be a prolonged duration of effect for some nitazenes; anecdotal reports suggest some analogues cause unusually long sedation and recurrent toxicity. Standard hospital toxicology screens often do not detect nitazenes (they require specialized mass-spectrometry tests), so cases might be missed or misidentified as fentanyl overdoses unless advanced testing is done.

Management:

Treat nitazene poisoning as an opioid overdose – naloxone is the first-line antidote, and lifesaving if given in time. However, because nitazenes may be extraordinarily potent, multiple or high doses of naloxone might be required to counteract their effects. Emergency responders should ventilate the patient (provide breathing support) as needed and not be dissuaded if initial naloxone doses don’t fully revive the individual – continue aggressive support. In the hospital, patients may require prolonged naloxone infusions and mechanical ventilation until the drug clears. Healthcare professionals should also be aware of the presence of nitazenes. Between 2019 and 2021, nitazene-related overdose deaths spiked in some areas (one report from Tennessee noted a fourfold increase, mostly due to metonitazene by 2021). Raising awareness can prompt more appropriate testing and reporting. As with any opioid use disorder, follow-up with addiction treatment and harm-reduction (like drug checking services, if available) is key – but the novelty of nitazenes means many people (including clinicians) are still unaware of this threat.

Not just opioids are evolving – a wave of novel sedatives is also emerging. Chief among these are designer benzodiazepines (sometimes dubbed “designer benzos” or “street benzodiazepines”), which are unapproved or chemically tweaked benzodiazepine drugs often sold online or mixed into illicit pills. Examples include clonazolam, bromazolam, flualprazolam, and etizolam. These substances produce sedative-hypnotic effects similar to prescription benzodiazepines (like Xanax or Valium) but are often more potent or longer-acting, and come with unpredictable purity. Because they are cheap to produce and not explicitly scheduled in some jurisdictions, they have proliferated in the illicit drug supply.

Risks and clinical effects:

Designer benzodiazepines can cause classic benzo effects – drowsiness, dizziness, slurred speech, loss of coordination, and heavy sedation – progressing to respiratory depression or coma in overdose (especially if combined with opioids or alcohol). Users often have no idea they’ve taken a benzodiazepine, since these drugs are frequently found as adulterants in opioid “downer” mixtures (the street term “benzo-dope” refers to fentanyl laced with benzodiazepines). This combination is particularly dangerous: benzodiazepines amplify the risk of death when used with opioids because they compound respiratory depression and can make opioid overdoses harder to revive (naloxone does not reverse a benzo). In Pennsylvania, for example, authorities noted a growing number of overdose deaths involving designer benzodiazepines – these drugs contributed to 59 overdose fatalities in 2022, jumping to 147 in the first half of 2023. Bromazolam (a Xanax analog) was the most common culprit in 2023, overtaking etizolam which was more common in prior years.

Management:

An overdose on these sedatives presents with excessive CNS depression: the person may be extremely hard to wake, with slow breathing, but often maintains normal pupil size (unless an opioid is also on board). Treatment is largely supportive – ensure adequate breathing and blood pressure. Flumazenil is an antidote for benzodiazepines, but it’s rarely used outside of controlled settings because it can trigger seizures, especially in patients who are dependent on benzos or who co-ingested pro-convulsant drugs. In most cases, patients are observed until the sedation wears off, with airway support as needed. Given the frequent combination with opioids, naloxone should be administered if any sign of opioid involvement – it won’t affect the benzo, but could reverse an unrecognized opioid component. Importantly, these novel sedatives often lead to prolonged withdrawal syndromes in dependent users. Healthcare providers should be alert for withdrawal symptoms (anxiety, tremors, seizures) and treat appropriately (often with long-acting benzodiazepines under medical supervision).

Beyond benzodiazepines, other novel sedating substances have emerged. One example is tianeptine, a drug used as an antidepressant in some countries but sold in the U.S. as a supplement (nicknamed “gas station heroin”). Tianeptine at high doses can activate opioid receptors and cause opioid-like highs, leading to dependence and withdrawal similar to opioids. Though not a benzodiazepine, it’s another unregulated sedative-like drug causing poisonings. In Pennsylvania, tianeptine was linked to a few overdose deaths in 2022–2023. The key lesson is that the spectrum of “downers” is broadening – any unexplained sedation or overdose should raise suspicion for these novel street drugs. Always involve a poison center or medical toxicologist for guidance on unusual cases.

Synthetic cannabinoids – often misleadingly called “synthetic marijuana,” and marketed under names like K2, Spice, Kush, or herbal incense – continue to pose an evolving poison threat. These are laboratory-made chemicals that activate cannabinoid receptors in the brain, but far more powerfully and unpredictably than natural cannabis. Early versions (JWH-018, etc.) emerged over a decade ago, but chemists keep creating new-generation synthetic cannabinoids to stay ahead of legal bans. The result is a constantly changing array of substances (e.g., MDMB-4en-PINACA, 4F-MDMB-BINACA, ADB-BUTINACA, and many others) being sprayed onto plant material and sold to unsuspecting users.

Clinical presentation and risks: Despite being marketed as “legal weed” or a cannabis substitute, synthetic cannabinoids can cause severe, life-threatening effects. Common symptoms include extreme agitation and anxiety, paranoia, hallucinations, delirium, and often tachycardia (racing heart) and hypertension. Many users experience nausea, vomiting, and seizures after using Spice/K2 – effects not typical of natural marijuana. These drugs have also been linked to acute kidney injury and, in some cases, heart attacks or strokes in young people. Toxicity varies by batch because the specific chemical (and the dose sprayed on the plant material) is inconsistent. Some batches have caused clusters of overdoses in communities, with symptoms like loss of consciousness or even cardiac arrest. In addition, standard drug tests do not detect most synthetic cannabinoids, so clinical diagnosis can be challenging – it relies on history or suspicion of use.

One particularly dangerous event involved synthetic cannabinoid products contaminated with the rat poison brodifacoum. In 2018, hundreds of users across the U.S. developed unexplained bleeding because the Spice they smoked was laced with this long-acting anticoagulant. Patients showed up with bleeding gums, blood in urine, and internal hemorrhages. This prompted a CDC alert. Even though that was an unusual case, it underlines that you never really know what’s in these products – they’re not tested for safety, and can contain potent drugs or even poisons that cause completely unrelated complications. In fact, a recent alert in New York warned of K2 packets found to contain fentanyl or other opioids (creating an even more lethal combination).

Management: Treat symptoms supportively. Agitation or seizures from synthetic cannabinoids are typically managed with benzodiazepines (like lorazepam) to calm the patient and prevent injury. Severe psychosis may require antipsychotic medications, but use with caution due to possible cardiac effects. If a patient has persistent vomiting, IV fluids and antiemetics are given. In the rare event of a synthetic cannabinoid causing cardiac or respiratory arrest, standard advanced life support measures apply. Notably, there’s no antidote – this isn’t a cannabinoid that naloxone or any reversal agent can fix, despite the “marijuana” nickname. For the brodifacoum-type cases, treatment required vitamin K for weeks to months to restore clotting factors; thus, if you encounter a synthetic cannabinoid user with bleeding, alert the poison center immediately. Overall, prevention is tough because these products are often sold legally in stores or online with innocuous packaging. Public education is crucial: people need to know that “fake weed” can be far more dangerous than real cannabis. As of early 2024, U.S. poison centers were managing numerous exposure calls for synthetic cannabinoids (91 calls in the first two months of 2024 alone) – indicating the problem is very much ongoing. If you or someone you know uses these products and develops unexpected symptoms, get medical help immediately and let the healthcare providers know about the suspected product.

In controlled pharmaceutical settings, safety is built around Paracelsus’s principle that “the dose makes the poison.” Still, the illicit market removes dose control entirely, making ultra-potent opioids dangerous even to people who did not expect high exposure.

Fentanyl is already the deadliest opioid in America’s drug supply – but its chemical cousins, the fentanyl analogues, can be even worse. Fentanyl analogues are modified versions of fentanyl that often have equal or greater potency. A notorious example is carfentanil, an analog originally created as an elephant tranquilizer. Carfentanil is estimated to be 10,000 times more potent than morphine and about 100 times more potent than fentanyl. In practical terms, a nearly invisible speck of carfentanil can be a lethal dose for a human. Other fentanyl analogues that have appeared in street drugs include acetylfentanyl, sufentanil, furanylfentanyl, and para-fluorofentanyl, among others. These analogues are sometimes referred to as “fentalogs” or “fentanyl-related substances.”

Why are fentanyl analogues showing up?

Illicit drug manufacturers churn out analogues for the same reasons as other novel drugs: to stay ahead of legal controls and to maximize potency (which increases profit). Carfentanil in particular grabbed headlines around 2016–2017 for causing clusters of fatal overdoses. After a brief lull, it has resurged – the DEA reported carfentanil reappearing in 2023 and being detected in 37 states, with overdose deaths rising sevenfold (from 29 deaths in early 2023 to 238 in early 2024). Traffickers have pressed carfentanil into fake prescription pills or mixed it into fentanyl powder to boost strength. The person using these drugs typically has no idea; a dose they could survive yesterday might be fatal today if it contains a hot spot of carfentanil.

Clinical effects:

An overdose on a fentanyl analogue looks like a severe opioid overdose – respiratory arrest, unconsciousness, pinpoint pupils – but it can onset extremely fast and be very hard to reverse. Carfentanil’s binding affinity for opioid receptors is extraordinarily high, which means naloxone may be less effective or shorter-acting against it. In practice, first responders have described needing multiple naloxone injections (even 8, 10, or more doses) to counteract suspected carfentanil overdoses, whereas a typical fentanyl overdose might reverse with 1–2 doses. Other analogues can also have varying durations; some might stick around longer in the body, leading to re-narcotization (the patient improves with naloxone only to crash again once it wears off).

Clinical experience shared by clinicians suggests some carfentanil exposures may have a prolonged clinical course, with ventilation support needed for many hours even after initial reversal efforts.

Because some fentanyl analogues have very high μ-opioid receptor affinity, patients may require repeated naloxone dosing and close monitoring, with ventilation support prioritized throughout.

A practical pitfall: many hospital “opioid screens” (immunoassays) mainly detect morphine-class opioids and may not reliably detect fentanyl or carfentanil, so a negative screen should not override clinical suspicion.

Management:

Naloxone remains the lifesaving treatment, but be prepared to use high doses and continuous monitoring. If you suspect a super-potent opioid like carfentanil, call for advanced medical help immediately – the person might require IV naloxone infusions and ventilatory support. From a first-aid perspective, focus on breathing: rescue breathing for the person if they are not breathing, while waiting for naloxone to kick in. Importantly, protect yourself as well; while the risk of first responders experiencing opioid toxicity from contact is extremely low, it’s wise to use gloves and avoid direct contact with any unknown powders. In hospital care, patients with carfentanil exposure may need prolonged ICU stays. Also, toxicologists sometimes employ laboratory testing to confirm unusual analogues (which can help public health officials track emerging patterns).

It’s worth noting that many fentanyl analogues are temporarily controlled by class-wide emergency scheduling in the U.S. However, permanent legislation is still catching up, and new analogues keep appearing. Public awareness campaigns are stressing that any pill or powder from a non-pharmacy source could contain a deadly fentanyl analogue. The adage “One pill can kill” is especially true now. If you see news about “gray death” – that term refers to a dangerous opioid mixture often containing potent analogues like carfentanil. Bottom line: fentanyl analogues represent an even more frightening evolution of the opioid crisis, and they require a rapid, aggressive overdose response. Always have naloxone accessible if you or someone you know uses opioids, illegal or prescribed.

Amid the drug-related threats, natural toxins are also an emerging concern – specifically, poisonous mushrooms finding their way into people’s meals due to foraging trends and social media challenges. Two phenomena are at play: amateur foragers misidentifying wild mushrooms (sometimes encouraged by TikTok or online “forage culture”), and a trend of “microdosing” or consuming exotic mushrooms (like Amanita species) for purported wellness benefits. Both have led to an uptick in poison center calls and ER visits.

Foraging gone wrong: In recent years, there’s been a growing interest in foraging for wild foods, including mushrooms, as a natural or sustainable lifestyle choice. Unfortunately, identifying mushrooms is notoriously difficult – even apps or well-intentioned online groups get it wrong. Poison centers nationwide saw an increase of over 11% in toxic mushroom exposure calls in 2023 compared to the previous year, a rise partly attributed to more people gathering wild mushrooms. A dramatic example comes from Ohio, where a man picked what he thought were edible puffballs based on a phone app’s advice. They turned out to be Destroying Angels (Amanita bisporigera), one of the deadliest mushrooms in North America. About 8 hours after his meal, he developed violent vomiting and diarrhea – classic early signs of amatoxin poisoning. Amatoxins (found in Destroying Angels, Death Caps, and a few other species) destroy the liver. By the time patients reach hospital, they often have elevated liver enzymes and can progress to acute liver failure. In the Ohio case, doctors even told the patient’s family his odds of survival were slim. He was ultimately saved by an experimental antidote, silibinin, which is derived from milk thistle and can help block amatoxin uptake by the liver. Not everyone is so lucky – amatoxin poisonings frequently require liver transplantation if antidotes are not given early. Other foragers have died after mistaking deadly Galerina or certain Cortinarius mushrooms for edible ones. Even “mildly” toxic mushrooms can cause days of intense gastrointestinal distress. The key message: Do not rely on smartphone apps or casual advice to identify wild mushrooms. Even experts can be fooled, and the risk is simply not worth it. If you forage, do so with expert mycologists and cross-reference multiple credible sources. When in doubt, throw it out!

TikTok and the Amanita trend: Separately, a bizarre social media-driven trend has people consuming Amanita muscaria – the iconic red-and-white “toadstool” mushroom – in the form of gummies, chocolates, or dried caps. Videos on TikTok and podcasts in the wellness sphere have hyped microdosing these legal (in most states) mushrooms for supposed benefits like relaxation or lucid dreaming. Unlike psilocybin “magic” mushrooms (which are Schedule I controlled), A. muscaria is not illegal because it doesn’t contain psilocybin. It does, however, contain muscimol and ibotenic acid, which are neurotoxins. In small doses, muscimol is a sedative-hypnotic/deliriant; in larger doses, Amanita muscaria can cause confusion, hallucinations, seizures, profuse vomiting, and critical organ damage. Poison centers have reported a sharp increase in Amanita muscaria poisoning cases as these products gain popularity. In 2016, only 45 poisoning cases in the U.S. involved Amanita mushrooms; now poison centers are logging hundreds of calls each year related to Amanita or similar products. Some patients thought they were taking a benign “natural” supplement only to end up in the ER with seizures and cardiac issues.

One problem is mislabeling and contamination. Many over-the-counter mushroom gummies are sold as “proprietary blends” with no disclosure of ingredients. A CDC investigation in 2023 into a cluster of hospitalizations found that the supposed Amanita supplement also contained caffeine, ephedrine, psilocybin, and kratom (mitragynine) – a dangerous cocktail that was not listed on the label. This means users sometimes unknowingly ingest stimulants or other psychedelics in addition to muscimol, further complicating the clinical picture.

Clinical presentation and management: For amatoxin (Death Cap/Destroying Angel) poisoning, there’s typically a delay of 6–24 hours after ingestion before symptoms, which then start as severe gastrointestinal upset (vomiting, diarrhea) and can deceptively improve for a day before liver failure signs begin (~72 hours post-ingestion). If amatoxin poisoning is even suspected, this is a medical emergency – treatment involves prompt dosing of silibinin or high-dose penicillin (if silibinin isn’t available), aggressive IV fluids, and monitoring/co-managing liver function (including transplant evaluation). Activated charcoal might be given if the patient presents early, to bind residual toxin. With any wild mushroom ingestion, contacting a poison center can mobilize efforts to identify the mushroom species (often through expert mycologists) and guide specific therapy.

For isoxazole mushroom (Amanita muscaria/pantherina) poisoning, symptoms usually hit within 2 hours and include a mix of neurologic effects: confusion, delirium, muscle twitching, seizures, alternating between somnolence and agitation, and profuse vomiting. Treatment is largely supportive as well – benzodiazepines for seizures or severe agitation, IV fluids and antiemetics for vomiting, and monitoring. There is anecdotal use of physostigmine (a reversible cholinesterase inhibitor) for severe cases of anticholinergic-like delirium from Amanita muscaria, but this is for hospital specialists to consider. In all cases, never attempt to self-treat a mushroom poisoning – always get professional help. Many fatalities occur because people underestimate the toxin or delay seeking care.

Bottom line: The foraging and TikTok mushroom trends can be literally deadly. Stick to mushrooms from the grocery store or reputable growers. If you choose to experiment with wild or novel mushrooms despite the risks, at the very least educate yourself extensively and have emergency plans. And remember that “natural” does not equal safe – some of the deadliest poisons known come from nature’s pantry.

Some fentanyl analogues may produce prolonged respiratory depression, requiring extended ventilatory support.

High μ-receptor affinity can mean higher or repeated naloxone dosing, but airway management remains the primary concern.

“Opioid screens” may miss fentanyl-class opioids, so clinical suspicion should drive management.

Stay Informed on Emerging Poisons: The drug and toxin landscape is changing. Substances like xylazine, nitazenes, designer “benzos,” synthetic cannabinoids, fentanyl analogues, and wild mushrooms are causing new kinds of poisonings. Awareness can save lives – know that a severe overdose might not be just an opioid (it could have xylazine or a nitazene), and that “legal highs” or natural supplements can be dangerously deceiving.

Recognize the Signs: Understanding the clinical presentations is crucial. For example, xylazine causes deep sedation and wounds (“tranq” sores), nitazenes/fentanyl analogues cause rapid respiratory collapse that may resist standard naloxone doses, designer sedatives cause prolonged unconsciousness, and synthetic cannabinoid toxicity often involves extreme agitation or seizures. Amatoxin mushroom poisoning has a delayed onset with GI symptoms followed by liver failure. Early recognition leads to early treatment.

Respond Swiftly and Appropriately: If you suspect any poisoning or overdose, call 911 and administer first aid. Use naloxone in any suspected opioid-related collapse (it won’t harm a non-opioid case, and might be life-saving if an opioid is involved). For seizures or agitation, keep the person safe from injury. Do not delay seeking help – time is critical, especially in things like amatoxin ingestion, where an antidote should be given ASAP.

Consult Poison Centers: America’s Poison Centers' helpline, 1-800-222-1222, is a 24/7 free resource for the public and professionals. Don’t hesitate to call if you have questions or emergencies related to any toxin, drug or mushroom. These experts can provide immediate guidance on treatment steps and have the latest info on emerging substances. When in doubt, let the poison center help figure it out!

Policy and Prevention: At the community level, support efforts that educate on emerging threats, such as distributing naloxone kits, providing drug-checking services, and implementing regulations to curb contaminants (for example, new rules to control xylazine are being considered). Encourage friends and family to be skeptical of drug trends on social media – what’s “viral” could be lethal.

A recurring theme voiced by toxicologists is that today’s synthetic opioid risk can reach people far outside traditional risk groups, sometimes through unrecognized exposure, which is why rapid recognition, naloxone availability, and emergency response training matter.

In conclusion, staying safe in this new era of novel street drugs and toxins requires vigilance. We urge readers: stay informed, never underestimate a substance’s danger, and seek expert help in emergencies. If you or someone you know uses drugs, consider reaching out to healthcare providers about risk reduction. And if an exposure or overdose does occur, call Poison Control (1-800-222-1222) and get medical care without delay. By spreading knowledge about xylazine, nitazenes, synthetic cannabinoids, mushroom toxins, and more, we can hopefully prevent poisonings and save lives. Stay safe and informed – and remember help is always a phone call away.

Further Reading:

As the drug landscape continues to evolve, this article fits into a broader toxicology series on MedicalToxic.com. For frontline overdose care, “Emerging Threats in U.S. Emergency Rooms: Fentanyl Overdose and Synthetic Cannabinoid Dangers” and “New Challenges and Innovations in Treating Opioid Use Disorder Amidst the Fentanyl Crisis” explore how fentanyl has reshaped emergency medicine and addiction treatment, while “The Alarming Rise of Synthetic Opioids: What Healthcare Professionals Should Know” and “Nitazenes: The Hidden Opioid Crisis That’s Deadlier Than Fentanyl” drill down on the next wave of ultra-potent opioids. If you are seeing more cases involving K2, Spice or “paper dope,” “Synthetic Marijuana Unmasked: The Deadly Truth Behind K2, Spice, and Paper Dope” and “Inside the Synthetic Drug Surge: Why 2025’s New Threats Are Different” provide additional context on synthetic cannabinoids and mixed-substance street drugs. For readers worried about carfentanil specifically, “Carfentanil: A Chemical Weapon Disguised as a Veterinary Drug”, “Carfentanil Overdose: A Public Health Emergency”, and “Exclusive Interview: A Conversation with Carfentanil” take a deeper look at this uniquely dangerous analogue, and for the mushroom and psychedelic side of the story, “Psychedelics in 2025: What’s Evidence-Based, What Isn’t, and How to Counsel Patients”, “Hidden Dangers of Microdosing Psilocybin: New Research Reveals Unexpected Risks”, and “Diamond Shruumz™ Brand: A Growing Public Health Concern” cover the clinical and public-health implications in more detail.

© All copyright of this material is absolute to Medical toxicology

Dr. Omid Mehrpour (MD, FACMT) is a senior medical toxicologist and physician-scientist with over 15 years of clinical and academic experience in emergency medicine and toxicology. He founded Medical Toxicology LLC in Arizona and created several AI-powered tools designed to advance poisoning diagnosis, clinical decision-making, and public health education. Dr. Mehrpour has authored over 250 peer-reviewed publications and is ranked among the top 2% of scientists worldwide. He serves as an associate editor for several leading toxicology journals and holds multiple U.S. patents for AI-based diagnostic systems in toxicology. His work brings together cutting-edge research, digital innovation, and global health advocacy to transform the future of medical toxicology.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). What You Should Know About Xylazine.

https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/about/what-you-should-know-about-xylazine.html

CDC Health Advisory / Pennsylvania Department of Health. Emerging Substances in the Illicit Drug Supply (2024).

PDF: https://www.pa.gov/content/dam/copapwp-pagov/en/health/documents/topics/documents/2024%20HAN/2024-763-8-1-ADV-Emerging%20Substances.pdf

Pereira T et al. Nitazenes: The Emergence of a Potent Synthetic Opioid Threat. Molecules. 2025.

https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/30/19/3890

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). World Drug Report – Key Findings (Nitazenes & Synthetic Opioids).

PDF: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/WDR_2025/WDR25_B1_Key_findings.pdf

America’s Poison Centers. Synthetic Cannabinoids – Exposure Tracking & Fact Sheet.

https://poisoncenters.org/track/synthetic-cannabinoids

U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Carfentanil: A Synthetic Opioid Unlike Any Other (May 2025).

https://www.dea.gov/stories/2025/2025-05/2025-05-14/carfentanil-synthetic-opioid-unlike-any-other

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, PBM Academic Detailing Service. Fentanyl and Carfentanil (patient handout).

PDF: https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/AcademicDetailingService/Documents/508/IB10-1137Pain-PatientAD-FentanylandCarfentanilHandout_508Ready.pdf

CNN / Poison Centers via KOLO/WHSV. With rise of mushroom foraging comes spike in poisoning calls (Jan 1, 2024).

https://www.kolotv.com/2024/01/01/with-rise-mushroom-foraging-comes-spike-poisoning-calls-officials-say/

Prada L. People Are Microdosing Mushrooms—and Poisoning Themselves. VICE (Aug 25, 2025).

https://www.vice.com/en/article/people-are-microdosing-mushrooms-and-poisoning-themselves/