What Is FAERS and Why It Matters in Medical Toxicology

Omid Mehrpour

Post on 17 Dec 2025 . 10 min read.

Omid Mehrpour

Post on 17 Dec 2025 . 10 min read.

When you hear people talk about “signals” from post-marketing safety data, they’re almost always talking about FAERS – the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System.

For many clinicians and even medical toxicologists, FAERS is a black box: they know it exists, but they’re not sure what it contains, how to use it, or how much to trust the signals it produces.

This post is a practical guide to FAERS for toxicologists – what it is, what it does well, where it’s weak, and how you can realistically use it in medical toxicology and poison-center work.

FAERS = FDA Adverse Event Reporting System.

It is the FDA’s large, centralized database of:

Adverse event reports (AEs)

Medication error reports

Product quality complaints that result in adverse events

…for human drugs and therapeutic biologics.

The database is designed to support post-marketing safety surveillance for drugs and biologics after they are approved and in widespread use.

FAERS is built from spontaneous reports submitted by:

Manufacturers – required by law to report adverse events they become aware of

Healthcare professionals – physicians, pharmacists, nurses can report voluntarily

Patients and caregivers – via the MedWatch program, the FDA’s safety information and adverse event reporting system

In practice, FAERS mixes:

Mandatory reporting from industry

Voluntary reporting from clinicians and patients

…into one huge spontaneous reporting database.

FAERS is one of the largest pharmacovigilance databases in the world, with millions of reports. A recent NEJM perspective notes that the number of potential safety signals identified from FAERS has grown massively – from ~780,000 in 2011 to >2.1 million in 2023, reflecting both more drug use and more intensive signal mining.

A 2025 PLOS ONE paper describes FAERS as “one of the largest databases for gathering and evaluating ADEs associated with drug usage worldwide,” updated quarterly and drawing reports from healthcare professionals, patients, and companies.

At a high level, the pipeline looks like this:

The report is submitted

Via manufacturer reporting systems (mandatory)

Via MedWatch online or FDA paper forms 3500/3500B (voluntary)

Data are ingested into FAERS

Structured tables (DEMO, DRUG, REAC, etc.) store case-level data: patient demographics, suspect drugs, reaction terms (MedDRA), outcomes, and dates.

The FDA and researchers signal detection.

Disproportionality analyses (e.g., reporting odds ratios, empirical Bayes methods) identify drug–event combinations that are reported more often than expected.

Safety evaluators review clusters for biological plausibility, temporal patterns, and confounding factors.

Potential signals are summarized in public lists.

FDA publishes “Potential Signals of Serious Risks/New Safety Information Identified from the FAERS Database” by quarter.

These lists are not proof of causality; they are starting points for deeper evaluation.

Regulatory action (or not)

For some signals, the FDA later issues label changes, warnings, or Drug Safety Communications.

For others, the FDA concludes that no regulatory action is required; those signals are moved to the archived reports list.

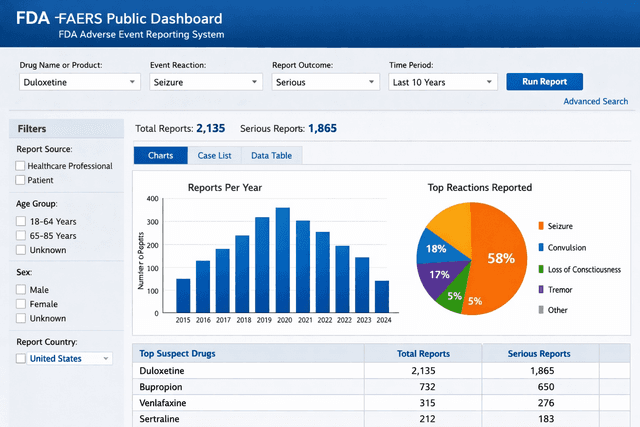

The FAERS Public Dashboard is the FDA’s interactive front-end for this database:

It lets anyone query FAERS data in a user-friendly way

You can search by drug name, reaction term, outcome, time period, and more

It’s intended to “expand access of FAERS data to the general public”

🔗 FAERS Public Dashboard:

https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fdas-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers/fda-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers-public-dashboard

Historically, FAERS data were posted in quarterly batch files. In 2025, the FDA began daily publication of FAERS adverse event data for some product categories (e.g., cosmetics) via a real-time public dashboard.

A September 2025 announcement describes a real-time adverse event dashboard that updates daily to reflect the most recent submissions.

Another August 2025 note states that daily FAERS updates for adverse event data have begun, enabling near-real-time monitoring.

For medical toxicologists, this matters because signals can emerge more quickly than under the old quarterly-only model.

FAERS is not a toxicology database in the classic sense, but it still has valuable uses for medical tox and poison-center work.

Because FAERS pulls in reports from across the country (and globally), it can show unusual patterns with marketed drugs well before RCTs or cohort studies catch up.

Examples of how this helps tox:

Novel toxicity phenotypes

Unexpected hepatotoxicity (DILI) or pancreatitis signals

New arrhythmia, seizure, or serotonin syndrome patterns

Non-overdose toxic effects of familiar drugs

For instance, FAERS-driven signal detection has previously led to warnings about drugs associated with torsades de pointes, SJS/TEN, or fulminant liver failure.

A 2025 review emphasizes that FAERS-based signal detection remains a cornerstone of the FDA’s early-warning system for post-marketing safety issues – even though it’s imperfect, it’s often the first place a new toxicity pattern leaves a trail.

Say you’re seeing:

More bupropion-related seizures in overdose, or

Unusual hypoglycemia with a certain GLP-1 agonist, or

Recurrent QT prolongation with a less-famous antiemetic

You can:

Use the FAERS Public Dashboard to look up that drug

Filter by relevant reaction terms (e.g., “seizure,” “hypoglycaemia,” “torsade de pointes”)

Then assess if there is a disproportionate number of reports related to that drug when compared to other medications.

It won’t give you insight, but it can reinforce (or challenge) your local experience.

When you write:

Practice guidelines

Review articles

Educational content for poison centers or EM residents

FAERS data (and FDA’s potential-signal lists) let you:

Document that the FDA has identified a formal signal

Show that a particular adverse effect is not just “one weird case,” but part of a larger pattern.

Anchor your recommendations in regulatory-level safety concerns.

For example, the Q1/Q2 2025 FAERS signal lists multiple novel agents and adverse events under review; citing them lends weight to your discussion of emerging drug toxicities.

Growing numbers of papers are using FAERS for real-world pharmacovigilance studies, especially:

Characterizing DILI profiles

Rhabdomyolysis signals

Safety of new anticoagulants, antiepileptics, or oncology drugs in real-world use.

This kind of work overlaps heavily with clinical toxicology, especially when you are:

Studying dose-independent toxicities of therapeutic drugs

Designing guidelines for managing serious adverse drug reactions (ADRs)

FAERS is powerful, but it has serious limitations that every toxicologist should keep in mind.

Multiple methodological papers emphasize that FAERS suffers from:

Under-reporting – many ADRs and overdoses are never reported

Duplicate reports – same event sometimes reported by manufacturer and clinician

Incomplete data – missing dosing, timing, comorbidities, and confounders

Variable quality in clinical detail

A 2024 analysis notes that, as a spontaneous AE system, FAERS inevitably contains omissions, underreporting, and inaccurate data, limiting precise risk quantification.

Another study stresses that the completeness of spontaneous reports is often insufficient for robust causality assessment.

Because:

The denominator (true number of people exposed to a drug) is unknown

Reporting rates vary by time, publicity, and country

Reports are influenced by media coverage and legal climate

…you cannot say “Drug X has twice the risk of event Y as Drug Z” just from FAERS counts.

FAERS is about signals, not exact incidence.

FAERS is built for FDA-regulated products:

Prescription and OTC medicines

Biologics

Some cosmetics and medical devices

For illicit drugs – fentanyl analogues, nitazenes, xylazine, “space oil,” etc. – you run into big problems:

No manufacturer is filing mandatory reports for street fentanyl, carfentanil, xylazine, etomidate vapes…

Clinician and patient reports are very sparse and often misclassified

These events are much better captured in poison center databases, medical examiner/toxicology reports, and syndromic surveillance, not FAERS

So if you want to study fentanyl adulteration in street drugs, xylazine wounds, or mushroom foraging outbreaks, FAERS is not your primary tool.

The FDA itself emphasizes that appearance on the FAERS signal list does not mean the drug has the listed risk – it simply means a possible relationship is being evaluated.

Reports may reflect confounding by indication (e.g., sick patients), co-medications, or reporting bias.

You still need clinical judgment, mechanistic plausibility, and ideally analytic studies (cohorts, case–control) to confirm causality.

For a typical use case:

“I keep seeing serious adverse events with Drug X. What does FAERS show?”

You can:

Go to the FAERS Public Dashboard

Search by drug name (generic and brand – be careful with spelling)

Filter:

Time period (e.g., last 5–10 years)

Reaction term(s) of interest (e.g., “overdose,” “poisoning,” “hepatic failure,” “rhabdomyolysis,” “torsade de pointes”)

Serious vs non-serious outcomes

Export counts or charts

Ask:

Is my suspected reaction even present in FAERS?

Is it common or rare relative to other drugs in the same class?

Is it already on the FDA’s Potential Signal list for that quarter?

This gives you context for your local cases.

FAERS is useful when:

You want to screen for possible drug–event pairs worth deeper investigation.

You’re planning a chart review or database study and need justification that the signal exists globally.

You want descriptive statistics: age, sex, reporting country, co-suspect drugs, and outcome patterns.

Many recent papers combine FAERS with longitudinal healthcare databases (claims, EHRs) to overcome the limitations of each data source and strengthen signal evaluation.

A short FAERS demo can teach:

The difference between anecdotes and systematic signal detection

The basics of pharmacovigilance and why just looking at RCTs is not enough

Why poison center data, ME data, and FAERS each see different slices of the drug-safety elephant.

For medical toxicology fellows, this is essential background if they want to conduct drug-safety research, work on guidelines, or consult with regulatory bodies.

For toxicology, the picture looks like this:

Poison centers / NPDS

Best for acute exposures, overdoses, and poisoning trends

Detailed clinical narratives

Includes illicit drugs, household chemicals, plants, bites, etc.

FAERS

Best for drug adverse reactions (approved meds) in the broader population

Helps identify rare or serious adverse effects not seen in trials

Weak for illicit drugs, strong for regulated products

Longitudinal healthcare data (claims/EHR)

Best for incidence estimates and risk quantification

Can link drug exposure to outcomes over time

Recent methodological work argues that combining spontaneous reports (such as FAERS) with longitudinal databases provides a more balanced, robust safety picture than either alone.

For a medical toxicologist, that means:

Use FAERS as a signal radar for therapeutic drug toxicity,

but rely on poison centers and toxicology services as your primary tools for acute poisoning and overdose.

FAERS is the FDA’s massive spontaneous adverse-event database, fueled by manufacturers, clinicians, and patients through mandatory and voluntary reporting.

It is excellent for detecting and characterizing rare or serious adverse reactions to approved drugs, and for generating hypotheses for further study.

It is not a real-world overdose registry, does not measure incidence, and is weak for illicit drug supply and many poisonings – that’s where poison centers and ME data dominate.

The FAERS Public Dashboard now gives you easy access, and 2025 updates are pushing toward near-real-time reporting, at least for some product categories.

For a medical toxicologist, FAERS works best as a complement:

To back up your clinical impression of a drug’s toxicity

To identify safety signals that might become tomorrow’s label changes

To enrich your research, guidelines, and teaching.

© All copyright of this material is absolute to Medical toxicology

Dr. Omid Mehrpour (MD, FACMT) is a senior medical toxicologist and physician-scientist with over 15 years of clinical and academic experience in emergency medicine and toxicology. He founded Medical Toxicology LLC in Arizona and created several AI-powered tools designed to advance poisoning diagnosis, clinical decision-making, and public health education. Dr. Mehrpour has authored over 250 peer-reviewed publications and is ranked among the top 2% of scientists worldwide. He serves as an associate editor for several leading toxicology journals and holds multiple U.S. patents for AI-based diagnostic systems in toxicology. His work brings together cutting-edge research, digital innovation, and global health advocacy to transform the future of medical toxicology.

FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS): Public Dashboard.

Adverse drug event surveillance and drug withdrawals in the United States, 1969–2002.

Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(12):1363–1369.

Empirical estimation of under-reporting in the U.S. FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS).

Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2017;16(7):761–767.